Typhani Harris | April 2014

With new standards on the rise, 21st century skills as a foundation, and the expectation that writing should be present across all disciplines, it is pertinent that we offer our students the opportunity to write within our arts classes. Although all of us can prepare a multitude of writing explorations for our students, historical, kinesthetic, expository, informative etc., a quick and easy way to infuse writing into your curriculum is through reflective practice. Enter the art critique!

My Visual and Performing Arts department came together a couple years ago to create a school wide expectation for writing an art critique. It has proven to be a valuable exercise for not only our direct students when observing professional, personal, or peer work, but also for students who attend our concerts and experience our art forms.

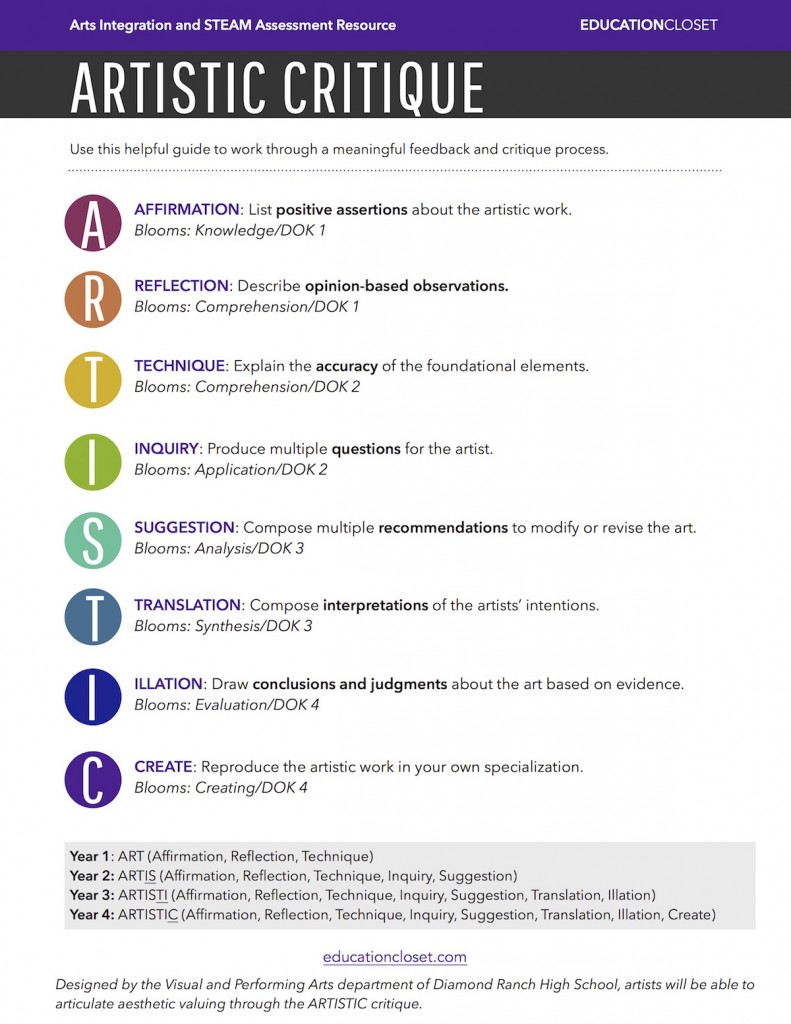

A- AFFIRMATION: this is a lower level of Bloom’s and Depth of Knowledge (DOK), requesting that students write affirmations of the work viewed. Students often confuse this with an opinion and want to explain how they “liked” or “disliked” something about the work. It is important that the distinction between affirmation and opinion is made. Regardless of whether a student likes or dislikes something, their affirmations should be made objectively on areas like structure, form, or technique.

R- REFLECTION: this is still a foundational level of both Bloom’s and DOK, requesting students to now make an opinion-based comment on the work with supporting details and evidence for their perspectives. This task allows students to subjectively provide opinions about the art, and justify their reasoning.

T-TECHNIQUE: still a lower level of Bloom’s and DOK, this section asks students to build on their prior knowledge by evaluating the technique used. Whether it is the technique of breath during a vocal song, the use of key during an instrumental presentation, the presence of shading in visual art, or the accuracy of a pirouettè in dance; educators can assess student knowledge of skills presented in class by their ability to evaluate those skills on a larger scale.

I-INQUIRY: this phase moves a little higher on Bloom’s and DOK as it is requesting that they apply their knowledge even more, by asking specific questions of the artist. To focus this task, educators can request that students provide questions regarding specific attributes. For example, if I am teaching lighting design, I may request that the students ask questions about the lighting design choices.

S-SUGGESTION: similarly this task requires students to build on their understanding by presenting possible suggestions to the artist. Again, this can be focused based on the specific skills you are working on in class.

T-TRANSLATION: at this point, we are asking a higher level of thinking from our students. Translation expects students to interpret the artists’ intention and purpose, as well as explicating the possible meanings behind the artistic choices.

I-ILLATION: as we move into the final tasks, we also move to the highest levels of Bloom’s and DOK. Illation asks students to draw conclusions and make judgements about the work based on evidence. Students can make technical, historical, or intention based conclusions, while using the previous tasks to provide evidence for their judgements.

C-CREATION: creation is now the pinnacle of Bloom’s and resides in the highest level of DOK. This section charges students to reproduce the artwork with license to alter artistic choices while staying true to artistic intent. This sections is particularly enjoyable when crossing artistic lines for example turning song into visual art or visual art into dance.

Ideally, the art critique process would begin with first year students utilizing ART and each subsequent year adding a new task, for example, second year students would work through ARTIS, third year students would work through ARTISTI, and in the final year students will practice all areas ARTISTIC.

It is not uncommon for administrators to struggle speaking the language of art, so this offers a common ground for arts educators and administrators. Although, as arts educators we know that the predominant form of assessment in the arts is an evaluation of a product or performance, however the education world often seeks assessment in the form of a “test” or an “essay”, and this accomplishes both. Additionally, students’ artistic language also grows through the practice of this art critique.

Reference:

Harris, T. R. (2013) ARTISTIC Critque: a practical approach to viewing dance, Journal of Dance Education, 13:3, 103-107.