ART WORKS FOR TEACHERS PODCAST | EPISODE 154 | 33:38 MIN

When Struggle Becomes Strength

Our students’ future depends on more than test scores. Stanford’s Jo Boaler is with us to reveal why struggle is the secret ingredient for deeper learning… and why now is the time to change how we teach.

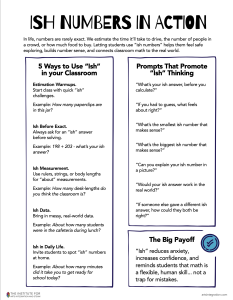

Enjoy this free download of the Ish Numbers in Action resource.

Hi, Jo, thank you so much for joining me today.

Jo

Thanks for having me.

Susan

Absolutely. So I know a lot about your work from I have good friends who are math specialists and who are coordinators and love the things that you’ve shared. But for people who maybe not are not like in the math world, so to speak, could you tell us a little bit about yourself and what led you to the work that you’re doing now?

Jo

Sure, yes. So I’m a professor at Stanford in the School of Education. I’ve specialized mainly in mathematics learning. I started my career as a teacher in London schools in the UK before I decided to study for a doctorate and then got lured to Stanford where I’ve been working most of the time. I did go back to England a few years ago, then came back here.

But it was about 10 years ago, I met Carol Dweck and she and I agreed that, you know, mindset was really important, but we should really do more to get it to teachers because up to that point, she’d really shared it as interventions for students. I made an online class called How to Learn Maths that got a lot of the evidence about mindset and about our brains growing and changing and better ways to teach maths.

I wasn’t sure if anybody would take it. made it when the MOOCs were just coming out. It was all very new. But 30,000 teachers took it that first summer. And it started to spread around. And then teachers were coming back to me saying, OK, what now? What can I have now? So this is when I formed U-Cubed with a district leader I was working with at the time, Kathy Williams.

We made this platform to keep getting the ideas out. Ten years on we’ve had millions of people visit the platform, use the materials and I know that teachers don’t have time to read academic papers and so this isn’t a platform where we share research. Well we do share research but we also translate that research into lessons that teachers can use and videos that they can share with their students.

Over that time frame, I’ve also written a few books. Mathematical Mindsets was the one where I really got these ideas out in the first place. And I wrote that about 10 years ago now. I followed that with a book called Limitless Mind because a lot of the readers of Mathematical Mindsets said to me, you have to get this out to more people, not just maths teachers, not just, you know, also administrators, other teachers, parents, people who won’t read a book with maths in the titles. that was when I wrote Limitless Mind and really tried to extend the ideas to all subjects, but also to life. Yeah, and so here we are. And that’s about me.

Susan

I love this background about your work because I’ve actually, I told our podcast producer behind the scenes that I referenced you in my upcoming book in chapter five, all about the art and science of flow. And I talk about your ideas around mathematical mindsets and being able to allow students the creativity and flexibility to build those mathematical mindsets. But for people who maybe don’t know what we mean by that, I know.

Lots of people know what growth mindset is, but when they hear math, they still have this preconceived notion of I’m not a math person or I can’t do that. And I know that a lot of your work challenges that idea. So can you talk to us a little bit more about what mathematical mindset really means and how we all have one?

Jo

Yes, so I realized pretty early on that it doesn’t really work to share mindset messages with students telling them you can learn anything, you can grow and learn and then deliver teaching as short closed questions with one answer, one fixed method. And when students look at it and go, I can’t learn, don’t see how, you know, these messages don’t mean anything to me. So we’ve been sharing for a long time that mindset needs to be embedded in teaching and in the culture of schools and in maths what that really means is opening up those questions so that students have space to discuss them with each other to draw to build things and that’s when those mindset messages can really take root so we’ve been sharing that a mathematical mindset means changing your approach to maths as well as just sharing ideas about mindset.

Susan

I love that. And one of the things that I really admire about your approach is the way that you use creative visual side of math. And I never got that as a student, right? It was always formulas and I didn’t understand why letters are mixed up with numbers. When we got to algebra, that was a whole other thing. So can you talk us through a little bit about how you are encouraged, the visual side of math, what that looks like, maybe practically in a classroom and maybe even how teachers can engage with that?

Jo

Sure. Yeah, one of the things we share on U cubed and I share with teachers I work with is that all of maths can be visual. Doesn’t have to be this subject of just numbers and procedures. And in fact, I share it in my latest book, which is called Mathish, research that, where they’ve looked at the brains of mathematicians and compared them with other academics.

And they find the difference is mathematicians have these very active visual pathways that are using visual thinking in all the maths they do. But we don’t encourage that for kids normally. We’ve made maths just a subject about numbers and procedures. So you can make anything in maths visual. And I love to share with people algebra that’s become visual where students are looking at patterns and understanding the structure of algebra. But any number question.

A simple one I can share is students in classrooms everywhere are given problems like, what is the area of an 18 by 3 inch rectangle? So their task is to do a multiplication to say 18 times 3. Whereas you could just as easily say to students, how many rectangles with an area of 24 can you make?

So now students are having to think about length and width, they’re drawing them out, they’ve got different rectangles, there are many different answers to the problem. So that’s part of the, that’s the approach we share. Let’s open up maths, make it so that there are lots of ways to get there. And visual thinking is a really important part of it.

Susan

Yeah, you mentioned algebra and being able to visually create with patterns for algebra. I have never in all of my years on this planet heard that algebra can visually be represented in those kinds of ways. So that makes me excited actually, because I truly, one of those, I’m just one of those people that I, math is a stuck point for me, just because it was given to me in cheat codes, right?

Jo

I’m sorry and I know that you’re not alone. Yes, we…

Susan

Right, right. And so that’s exciting. And so I’m curious, have you seen ways in which the arts in particular, either visual art or music or theater or dance in any kind of way has been able to be used in math classes that have been effective in your opinion?

Jo

Certainly, yeah. And just before we leave the topic of algebra, I should share with you that I share this visual approach to algebra with teachers often in conferences and workshops. And a few times I’ve had teachers cry while working on these visual algebra problems. And the reason they’ve cried is because they’ve worked on the visual, seen the algebraic structure, come up with their own quadratic expression, and then said to me, you know, I just went through hundreds of hours of algebra classes never thinking I could solve a quadratic, let alone come up with my own that I see visually, that I understand the connections. So on our website, on U cubed, we have four weeks of algebra lessons completely free that introduce algebra as this visual finding patterns subject that is so important for students. But to get to your broader question about the arts,

So much. mean, we have a section of U cubed as well that’s on art and mathematics. And I feature actually a teacher who I first met in my teacher classes at Stanford called Diarra Busso who was from Nigeria. sorry, from Senegal was, you had loved growing up in Senegal and all the artistic fashion work she’d done with others, come to the US, been very mathematical, worked in Wall Street, but missed that art and then came into my teacher class and said, could I combine art and mathematics? What do you think about making a whole line of fashion using algebraic equations. And I was like, yes, you know, fantastic. She now makes, has a line of clothing that is solved in Bloomingdale’s, Nordstrom, a lot of really great fashion places. She’s been featured in Vogue and all of her designs are based on algebraic patterns. Absolutely. Also, my newest, newest book actually is about data and how important it is to bring data into teaching. And one of the things we’re excited about with data is students can do undergo a process called sonification where they actually play the data as music and there’s a whole line of work around this now where people are making great works of literature into music so you can hear the patterns and

We were actually in a classroom recently where students were doing our basketball project that we have on UQ to where they’re using data from basketball. And one of the students was letting the girls in his group do all the work. And we spoke to him and said, what’s going on? And he was like, yeah, numbers, you know, I don’t need to do that. They can do it. And… was telling us about his love for music and then together we discovered this sonification feature and he was hooked. So maths, totally very strong connections with music and maths. The pattern, the flow.

Dance, one of the big things I share is the importance of times of struggle, how that’s actually really good for your brain. And I love James Nottingham’s pit of struggle. I’ve shared that a lot with teachers and some teachers were recently telling me that they’ve taken the pit and made, and students are doing interpretive dance around it. So, that is exactly it. Math should be this multi-dimensional subject that we see in dance and art and music and building and visuals. And then students love it. So why don’t we do that?

Susan

Yeah. So I want to dig into a couple of these things. So what specifically is sonification? As a music teacher, I know what it is, but for people who may not understand that word or know what that term is, what is that and how, why does that hook students in such a way that makes them curious to learn more, do you think?

Jo

Well, I’m not an expert, but I believe sonification is taking forms of information and putting it into sounds. So they have found ways to turn a number and data into sounds. One of the things we highlight in our data minds book is they have taken space up in the sky and looked at how when things travel through space, they’ve taken like a large amount of space, it’s a NASA project, I think, and turned it into sound. So you can listen to the variations in space and the different aspects that are presented. So yeah, it gives people a different way to access information and some people really like sound music. So it’s pretty exciting for maths and data, I think.

Susan

Yeah, and in your book on the news, the new book that’s coming out for about data, do you focus at all about data visualization? Because I know that that is a big topic right now. Yeah, I know that that’s a big topic right now. And I know a lot of teachers are very interested in what that looks like, how they can bring that into the classroom.

Jo

Yeah, yeah. Actually, we have something we talk about in the book and also is on our UQube site. We launched something a few years ago called Data Talks and we were using the structure of something in maths education called a Number Talk. what is a data talk is showing students a data representation, a data visual.

And just asking them what do you notice? What do you wonder? Really helps kids develop data literacy, helps them be able to interpret data visuals, which I think of as a protective strategy in education because young people are being sent data visuals all the time, you know, in an attempt to mislead them. So helping them develop this, being able to look at a data visual and unpack it. What is it really saying? Where did it come from? What do the axes mean?

But all of them, what we share are these incredible data visualizations that are beautiful and also show data in a much better way than we have in the past. know, they’re not just bar graphs and pie charts. They’re one of our most popular data graphs shows Steph Curry’s movement on the basketball court and how successful he is in different places shooting and it shows it on the court so you can actually look at when he’s over here it’s this successful and here and when this bit of the court is different in this way you could have shown that information on a bar chart but it you see so much more seeing it on the court so very exciting data visualization is really very exciting

Susan

Yeah, and I think it’s such a great access point in for many students who, again, are looking for a way to connect mathematically. just, and it lights up a different area for them. In your book, Math-ish, you tend to invite us to take a broader view of math, and one that’s more flexible and connected to real life. And we’ve kind of been talking about this, but outside of the arts, what does that look like in practice?

Jo

Well, one of the connections with the world that I introduce in Math-ish is actually the idea of ish numbers. And I make an argument that, you know, in the real world when we use maths, we very often use what I call ish numbers. Like we’re working out how much paint we need to paint a room or how many people are in a crowd or how long the drive is, the airport, you I could go on and on. But in classrooms, maths is always very precise. And that’s what scares children that, you know, they are afraid of getting it wrong and the precision really holds up a lot of teachers. So I point out that actually, you know, we know that many students don’t have number sense and they just get lost in calculations. That a really good strategy is to ask kids before you ever calculate, give me your ish number. So

You know, we’ve always had estimation in maths, but I know from teaching that kids hate to estimate and they think it’s just another method and why, why do you bother? But when you ask them what’s your ish number, it’s kind of magical. Something happens, they become more free, they’re more willing to share their thinking. So that’s one of the ways I say, you know, having kids come up with ish numbers, it helps them with number sense, but… also makes a connection to the world for them because they know that that’s the maths they use in the world. But yeah, we can bring in the world in so many ways. I do have a discussion in Math-ish about highlighting the, you know, the culture and the history of mathematics, where maths came from. Fascinating and interesting for kids. Bringing data into maths immediately gives that real world connection and is important for other reasons. So, yeah, it’s not difficult to do this. Now, I will say, though, that many teachers feel kind of beholden to follow the textbooks their districts have given them and the textbooks don’t do this. So what we find is teachers who are giving kids this richer, more multidimensional maths experience are often doing that by stepping away from the textbook and bringing in other materials. So I would love it if we actually got our publishers to pay attention to this and not give teachers that extra work.

Susan

I understand. I understand. Yes, I understand more than you think because I think we teachers who are trying to implement STEAM are doing something similar that it’s not embedded in their curriculum as is and so they’re kind of using it as an offshoot and the tour as a way in for students. And so I feel your pain there. So my question, guess around that. Yeah, is it.

Jo

Yeah, it’s hard work. I mean, it’s harder for teachers to do that.

Susan

Yeah, we know that these things work, right? We have the research around them. We know that the tools like this, using math-ish numbers, which I love the word ish, it’s just fun. And it makes it a little bit more playful. But using things like that, using techniques of bridging art and math together work. We know that these things work and yet curriculum developers are slow to put it into the curriculum for whatever reason. And I’m so curious.

How do you advise teachers to bring this in when perhaps they’re on a pacing guide and they’re very scared, honestly, to move or break away from what is written in that text?

Jo

Yeah. In Mathematical Mindsets, I actually have this set of advice for teachers. Okay, you love these ideas, but you’re stuck with this district textbook. What do you do? And I have these like, do this, do this or this. But one of them is your district textbook probably has kids doing a hundred of these questions. Instead of that, choose five and have the students talk about the solutions with each other, draw visuals. You don’t have to have the visuals in the book to ask the students, can you come up with a visual representation of that? You’ll be amazed at how great students are doing that when you give them the freedom and they get used to it. So you can open up maths yourself, even if you have this rigid district textbook. And I set out, you know, different ways you can do that.

Susan

Yeah, I think it’s so important that we do provide our teachers with the ability to, or the flexibility to understand that maybe what’s provided is just one way and that there are that our students need to unlock learning for them. One of the things in your research that I found really interesting was that you’ve kind of determined that little things like tracking and timed tests can actually limit learning and I remember those tests and my daughter has those recently and she hates them. What are some changes do you think that schools could or should consider to help students develop a healthier, more meaningful relationship with math?

Jo

Well, you’re right to highlight assessment. It’s extremely important and what the way teachers assess maths gives kids a very strong idea that that’s what maths is. again, lots on you cubed about shifting assessment from a fixed practice of grades and scores to a growth practice and maybe using rubrics and giving kids feedback on their learning, which is super beneficial. Time tests of math facts, which you just get rid of them. They have a lot of advocates, have people who love them and argue for them, but I have met too many people who’ve told me that they gave up on maths once they started doing timed maths tests. Even if they didn’t make them anxious, and for many people they do, but even if they didn’t…

It caused the kids I’ve spoken to to think, well, this is what math is, just like timed recall of facts that don’t have any connections or meaning. So I really want to do that. It was about 10 years ago that we released a paper on our website called Fluency Without Fear that goes through the research evidence on this and also shares lots of ways of teaching maths facts where kids see them visually and they’re connected and they learn them better. we’re about to work on that and re-release a 2025 version with some updated info. A lot of people have read that paper and a lot of teachers use the activities to help kids do time to do math facts. Sorry. And some assessment companies like the Smarter Balanced Park assessment took out their math fact testing when they read the paper. So I know it’s had impact out there in the world, which is great. I also get a lot of heat from the people who love time tests and want them to stay. So.

Susan

So I wanted, just, for briefly, I want to dig in this just a second because I know working with many math teachers, this is a division point, right, for many of them. The ones who advocate, this is what I hear a lot, is that without those math facts, without doing the time test this way, students are going to get behind on their numeracy, that they will not be able to move ahead in other math fields and, you know, specializations without that. And so what’s the counterbalance to that then?

Jo

So there was a little slippage in your words there which I appreciate from you because it is exactly what teachers say which is kids need math facts and time tests to teach them so we have to separate those two things. Sure, math facts can be helpful. Time tests? Why do we need time tests to help kids develop math facts? That is the question we raise. And as I said, the paper fluency without fear has a lot of cool activities where kids are learning math facts and they understand them.

So yeah, people who’ve come after me over the years totally misinterpret what we’re saying and say, Joe Bola says kids don’t need math facts and so they won’t be able to do all these number problems. We’re not saying that. We’re saying, if you’re gonna learn math facts, and you know, we could argue about how important they are, but if you want kids to learn math facts.

There are much better ways of teaching them. Blind memorization is not a good way of learning math facts. It leads to errors. It’s very fragile. What you want kids to have, they think of math facts. You want their brains to go to visuals that show skip counting, that show different ways of coming up with this math facts. That’s a strong memory. So, yeah, I’m glad you raised that case. This misconservative.

Susan

Well, that’s really helpful because that is what I hear a lot when I talk to different math teachers of different understandings. And many times the ones who advocate for both or confuse the two and link them together will say that math facts are time tests for math tests or for math facts lead to fluency or an indicator of fluency similar to when you’re looking at students who are reading, you know, sentences and how fast or slowly that they’re reading those sentences. But what you just shared really makes sense to me as a music educator because when there’s a very poor, poor structure in music that’s similar to that in math, that of blind memorization, of just memorizing a piece of music or memorizing the notes or memorizing any kind of theory behind it and without being able to break it apart, it doesn’t work. You might be able to perform it, but it doesn’t mean you understand it. And so I appreciate very much that that is similar in your work as well.

Jo

And that is why we called our paper flu- why we put the fluency word in. Fluency without fear. You can become fluent. Actually, I grew up in a sort progressive era in the UK. I never memorized math facts as a child. Never. We didn’t do that. We had no time tests.

I can do number problems as fast as anybody else, but I actually make connections with the numbers. It’s not a blind memorization approach, it’s a number sense approach. So I don’t even believe that it leads to faster number work. I think it leads to flawed number work when people take that approach.

Susan

For sure, for sure, because again, if you memorize something wrong or incorrectly, it’s the pathway correct. Yeah, and the pathway can just, I mean, it’s built then and to break it apart is so much more difficult. So, this has been fascinating as a chat today. Thank you so much. How can our listeners stay in touch with you and continue to follow your work and get your latest book?

Jo

Right. And you don’t know. You have no way of knowing it’s wrong.

Great question. Well, youcubed.org, you and cubed is our website. And we have workshops, come to us, workshop at Stanford or online, come connect with us. I have books, I mentioned Mathematical Mindsets, but my more recent book is called Mathish, if you’re a maths educator. If you’re not, Limitless Mind is the sort of translation book. And our most recent book is called Data Minds, also mentioned that we now have a little online tool that gets this maths to kids called Struggly, which is very popular with kids and teachers. Students get rewarded for making mistakes and struggling to help encourage that growth mindset. So there are lots of ways to follow and see our work.

Susan

Well, wonderful. We will put all of those in the show notes. I will be hopping over to you to take that algebra segment so that I can feel good about that. Thank you so much. And in the meantime, thank you so much for the work that you do and for continuing to kind of spread this message that math is for all. We really appreciate it.

Jo

Thank you. I appreciate that. It’s nice.