ART WORKS FOR TEACHERS PODCAST | EPISODE 137 | 38:48

The Biography of an Idea: How Creativity Really Happens

What if ideas had their own life stories? In this episode, Harvard researcher Edward Clapp reveals how creativity really works, and why it's less about genius and more about collaboration, agency, and systems thinking. This conversation will change how you teach, no matter what subject or grade you're in.

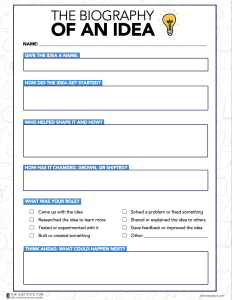

Enjoy this free download of The Biography of an Idea worksheet for students.

Well, hi Edward, thank you so much for joining me today.

Edward

It's a pleasure to be here. Thank you for having me, Susan.

Susan

Of course, of course. So I always like to start with our guests, asking them a little bit about what was your journey into education, into creativity? Share a little bit about yourself for us.

Edward

Yeah, sure. I'm happy to do that. So my name is Edward and I'm currently a researcher at a place called Project Zero, the founder and chief executive officer of a learning and development organization called the Next World Learning Lab. And the path that I took to kind of be in those places is that I started out in the arts and was a practicing artist for a while trying to make it in New York City.

And while I was doing that, I was also gigging as a teaching artist. Then gigging as a teaching artist turned out to be being an arts and education administrator and was doing all these sessions where I was facilitating workshops for arts educators and their teacher colleagues. And we were putting together these big workshops and these big learning communities. And somebody said to me one day, you you got to go learn from those people in project zero. I think you'd really dig it and you've got to go check that out. So that's exactly what I did. I started my graduate studies at the Harvard Graduate School of Education, became a research assistant at Project Zero right away. That turned into my doctoral studies there and now a principal investigator at Project Zero some almost 20 years later. So that's kind of the arc of that and the pathway to this work.

Susan

That's amazing. So now I'm curious your your arts background. Are you a visual arts artist, a musician, a theater guy? What's your media?

Edward

A little of this, a little of that. So my bachelor's of fine arts is in painting. So I have a visual arts background, but also have a master's degree in creative writing. So I kind of balanced those things out. And for a little while, for about four or five years, I worked with a colleague and we co-directed a off-off-off-off Broadway theater company in New York City called Collective Whole Productions, where I was the resident playwright and I worked with a colleague of mine who was the resident director. And once a year we put on a really independently sweat equity run kind of show. So little this, little that, but I mostly define or identify myself as a maker. A maker of things, a maker of stuff. Sometimes that's in the arts, sometimes that's in any number of half-finished home improvement projects here at my house in the North Shore, Massachusetts.

Susan

It all counts, you know, that's what DaVinci said, right? It all counts. So it's all what we're doing and constantly kind of putting our fingerprint, our creative fingerprint on the world, right? So now I love Project Zero, but I know that some of our audience members may not be as familiar with it as I am. So could you do us a favor and just kind of share a little bit what exactly is Project Zero and what do you research there?

Edward

Sure, sure, sure. That's a great question. So Project Zero is a research center at the Harvard Graduate School of Education. It was founded in 1967, so we're going on 60 years, by a philosopher named Nelson Goodman. And Nelson Goodman was also an art collector in the Boston, Cambridge area. And at the time, he was charged with studying the cognitive affordances of the arts. So in other words, what is cognitively beneficial about engaging in arts learning. And this would have been a time where the arts and arts teaching and learning was very associated with the emotive aspects of that work, the expressive aspects of that work. So he was researching the cognitive aspects of the arts. And at the time, you know, perhaps not entirely accurately, Nelson Goodman said, well, we really don't know a lot about that. So we'll call it Project Zero. So for better or worse, the name has stuck for almost 60 years.

And Project Zero continues to be a research center at the Harvard Graduate School of Education. It takes on many different shapes and sizes and has changed and evolved over those few decades. And our breadth of work has expanded beyond arts teaching and learning to include research on the intelligences, teaching for understanding, making thinking and learning visible, digital life and digital competencies, global and cultural perspectives civil and moral education. then the thing to get to your question, the things that I study include design and maker centered learning and creativity and innovation, entrepreneurship with a special angle towards early childhood education.

Susan

I think it's so helpful. actually think that not a lot of people know all of the things that Project Zero really covers. I know a lot of our audience are familiar with the thinking routines that came out of Project Zero, which are phenomenal, are so simple yet elegant in how they help us to kind of foster more of that creative thinking, but there is such a breadth of work that Project Zero really does cover.

What's interesting to me, I love how you said that you've studied innovation and creativity, and I know that you've studied how innovation happens. And so I'm really curious to dig into that. think people talk about innovation a lot in schools. It's something that seems to be like a buzzword of, yes, we want more innovation in our schools, but there's this kind of ethereal quality about how does that actually happen? So I would love your take on

Edward

Yeah, I'm going to come at that from two different angles. So one is to talk about a concept that my colleagues and I developed originally working with a cohort of educators in the United Arab Emirates in both Dubai and Abu Dhabi. And this was a project called Creating Communities of Innovation. It was a multi-year project where we worked with cohorts of educators at different schools. And each of those schools applied different curricula. And we were just exploring how they can innovate with their practice.

And we set up this structure for them to pursue and eventually developed a model along with our teacher colleagues that we called inquiry driven innovation. So an answer to your question there would be that innovation is a product of inquiring with your practice. So you can't just, or, you know, the idea is that you don't start with innovating with your practice. You start with looking closely at your practice, engaging in reflective practice, really understanding who you are, what's your context, and who are the young people you work with. And once you have a more firm understanding of those three things, you can then say, well, given all of that and what I do on a day-to-day basis, how might I experiment with my practice and change my practice? So that's one approach that we call inquiry-driven innovation. Another approach is something that my colleagues and I have developed over the years, both at Project Zero, but mostly other places that we call participatory creativity. And this is where I think there might be the most traction with your podcast and this whole notion of creativity is not being an individual endeavor, but rather being a socially and culturally distributed act that happens over time. So creativity from a participatory perspective is not the work of single individuals. It is especially not the work of people who are identified as individual geniuses but rather is the work of collective people or collective actors who might not even be people, including artificial intelligences, engaging in the development of what we call creative ideas over time. So participatory creativity is all about contributing to the winding path that an idea makes as it wends its way in the world over time.

Susan

Okay, so now I've got a lot of questions. I'm starting to ping on some of the things that you're sharing. So I guess maybe my first question is, and this is a clarifying question. So does creativity always have to be participatory or can there be creativity in isolation?

Edward

Creativity never happens in isolation. It's never the work of sole individuals. It is always socially and culturally situated. So I believe, and many of my colleagues believe, from a social culture perspective, from a participatory perspective, people are not creative. Kids are creative. There's no such thing as a creative individual. Ideas are creative. And when we take the locus of creativity and we move it outside the skulls and skin of individuals, and put it in a social space, that makes it possible for many people to participate in the development of creative ideas in a way that draws on many individuals' different talents, skills, background experiences, and cultural perspectives. So it tries to be a more democratic approach to the creative process and not this individualistic approach to the creative process.

Susan

So if creativity lives outside of us as humans and it's more around the ideas that it lives in capsulation with the ideas and that we can all participate, then I'm curious when people say that I am not creative or I am creative or that Mozart was born with a creative genius or, you know, Da Vinci, how do we explain from a research perspective how

Some people engage with creativity, maybe in ways that we hadn't seen before, where others feel like they can't engage with creativity or that they are just not creative.

Edward

Yeah, that's a great setup for this concept that we call the eight crises of creative participation or the eight crises of creativity. those all come from, well, five of them come from our cultural of individualism, and then a bunch of them also come from our cultures of power. But the version that you're talking about coming from our cultural individualism is if we have an individual approach to what creativity is, then we have to say it looks like this and is very narrow and that biases some people that make meaning of the world in those ways. Well, it alienates the majority of others who don't make meaning of the world in that way. So when you hear somebody say, well, I'm just not a creative person, they're referring to a means of being creativity that is outside their own meaning making. But instead, if we could say, creativity isn't the prominence of any one individual.

It doesn't belong to somebody. You aren't a creative person. You don't have creativity. Instead, you participate in creativity. Then that active participation opens up engagement and creativity to the wide breadth of people and the multiple ways they make meaning of their experiences and the various cultural perspectives they bring to the work. So it's not that Mozart way or Einstein way of thinking. That's one way of thinking. But it's the many ways that people contribute to the development of creative ideas. And I would argue even further, maybe controversially, that neither Mozart nor Einstein were creative either. They were participants in the development of creative ideas and they played specific roles. So something that's really important in the theory of participatory creativity is the concept of roles. And that is there's not one way to be creative, but there's many ways to participate in creativity. And when we engage in creativity,

We do so from the perspective of different roles, not just a single way to participate in creativity.

Susan

Okay, so give me some examples of what those roles might be.

Edward

Okay, great. Go to a soccer field with me right now or for your friends in England or elsewhere, a football pitch. Okay. So, and this is to one of your further, you know, further questions on your list that you shared in advance. Thank you very much about collaboration. I believe it's question. I can't spot it right now, but something there it is. Collaboration is key, a key theme in your work. No, it's not. So I am strongly against the concept of collaboration.

Mostly because of the English origins of the word. If we break down the word collaboration, it means to co-labor. Okay? So when we think colloquially about what collaboration means, and there's nuanced understandings of collaboration that are much more specific than this, but many people think collaboration is everyone doing everything together at the same time. Okay? And if… So I have younger children. I have a five-year-old and an eight-year-old. And if you went to see my five-year-old's soccer games, it would look exactly like that. Everyone going after the ball at the same time. That's collaboration. Everyone working together to get that ball. But that's not effective engagement in the game of soccer. If you go to a professional game, you know, somebody who really understands soccer will know that people go back and forth and they're playing different roles at different times, but it's not everyone going after the ball at the same time. So this whole idea that people play different roles,

But those roles are neither fixed nor uni-dimensional, but rather dynamic and ever-changing. And just to introduce some more language from the perspective of participatory creativity, we call that having a profile of participation. So there isn't just one way that you could participate in creativity, you know, which is the way that the theory of multiple intelligences is often misinterpreted, that you're intelligent in this one way. Well, yes, you are, but you're also intelligent in many other ways that make up your profile of intelligences and the same thing carries through with participatory creativity. You don't just participate in creativity in one way. There's multiple ways that you participate in creativity and those make up your profile of intelligences and, profile of participation. My apologies. And you go back and forth with how you participate depending on what's called upon you at the time and who else you're collectively working with.

Susan

There are so many different ideas that are coming up in this podcast episode that I'm so grateful for because again, I'm actively learning with you because I've never heard of this kind of exploration around creativity before. There's a lot of research out there about creativity that I've looked at and this is new to me. So I'm very excited as we're having this conversation and pardon me if I go off in different directions, but I'm… I have learned that sometimes the way that my brain works is also mimicking what my audience is thinking. So with that in mind, one of the things that you were talking about with the creativity in general and also why it's not an individual act is the idea of creative ideas. Where do the ideas spark them from? Do they come from the individual or where do they come from?

Edward

Individuals contribute to the development of those creative ideas, but they're not solely grounded in the work of one person. So another concept that we use in the practice of participatory creativity is something that we call the biography of an idea. And this is often very clarifying for folks. So if you think of somebody who is often identified as a creative individual or even a creative genius, if we use one of the most popular, you know, dead white guys, Albert Einstein, we can say, you know, he was a creative individual. There's something unique about his brain. It's being preserved in a jar somewhere for people to learn about it one day. And from that perspective, the individualist approach to creativity, there is this whole thing about, you know, well, how did Einstein's brain work or Picasso's brain work or Darwin's brain work or any of the other dead white guys?

When people study those individuals, they come up with these different narratives. They're telling the biographies or the stories of those individuals. But what we find when we tell the stories of those individuals is those individuals were as unique as the ideas that they're most known for. So there isn't any special sauce about developing creative individuals. So instead, we have to look at something else. So instead of telling the life story of a creative individual,

What if we told the life story of the idea that individual is most known for? So in the example of Albert Einstein, instead of looking at the biography of Albert Einstein to figure out, what was the secret sauce? Why is he so special? How did the neurons come together uniquely in his brain? Instead, if we told the special theory of relativity, we told the biography of that idea that he's most known for, we'll see that over the course of time, many people contributed to the development of that idea.

And many people played different roles in the development of that idea until Einstein gave voice to it and played this sort of, you know, role where he put it out in the world and it became known. But since that idea has continued to exist and other people have contributed to the development of that idea. So to break down or to kind of trace the history of ideas, we tell the biography or the life stories of those ideas. And they're just going to go back and back and back and back until we can't trace them anymore. And we'll see that many people contributed to the development of those ideas in many different ways. And when we tell the life story or the biography of an idea, we help young people understand there's not one way to participate in creativity. There's many ways that people have participated in creativity. And you might not see yourself, you might not recognize yourself as a young person when you look up at the posters of the creative individuals in your school, that might not look like you.

But when you start to unpack and see who the different people are that contributed to the development of those ideas, you'll see that there are plenty of people that you can associate yourself with and you can identify yourself within the story of a creative idea.

Susan

Yeah, yeah, I love this idea of a biography of an idea because as a musician myself, like that's my medium, right? I often think about Mozart, right? That you're three and you're composing these pieces and how much of it was composition versus mimicking. But when you look at many of his pieces, if you study them, like many professional musicians will, and break them apart, much of what Mozart actually produced was influenced by Haydn.

It was things that his own teacher looked at and had developed. And so Mozart just took them and twisted them a little differently. So it's a play on that biography of the idea of twisting the, and isn't that what all art making is, right? It's taking what you've seen and maybe putting your own spin on it or adjusting it in some way and playing with it to see what might happen, right?

So I'm curious about the intersection of creativity then and innovation. So we started talking about innovation in education and what that could look like and how that happens. What's the juxtaposition between the two? Because often we're hearing in schools that schools are irrelevant because we need to get students ready for the 21st century where there is creative thinking and critical thinking and collaboration and innovation and they're just coming out not being able to do any of it.

So what's that juxtaposition look like?

Edward

Yeah, so I'm not going to go too far down this path because I generally use creativity, innovation and invention, you know, kind of synonymously. So I don't make too many distinguishes between those. I know that some people say creativity is like coming up with something entirely new and innovation is tweaking things and experimenting with practice. You don't understand that, but I also don't believe there's anything that's entirely new, like you said with the Mozart-Hydin example.

I think that things build on themselves and develop over time. But what I will say to your question about what is the role of creativity or innovation within schools, I think it's to develop, and this comes from the work of Project Zero, it's to develop a sensitivity or awareness for the opportunity to influence change. So from the perspective of Project Zero, we have something there we call very fancily the triadic theory of dispositions. So a disposition is essentially a way of seeing and being in the world. It's a mindset. But the triadic theory of disposition says there's three different parts. There's the ability or the capacity to do something. So you're able to do something, know how to do something, you're deft in that way. There's the inclination or motivation to do that thing, you want to do that thing.

And then there's something they call the sensitivity or alertness to occasion. You know when to employ that talent or skill or ability or what have you. So to use a very silly example, I said again, have little ones, a five and an eight year old. They both know how to clean their room. So my son, Wolfie, and my daughter Penelope know how to clean their room. Okay, they have the capacity, the ability to do them something. Item number one but they don't always have the motivation or inclination to clean their room, right? But sometimes they do. Item number two, capacity inclination. But even though they have the ability to clean their room and they want their room to be clean, according to my wife and I, they might not always have the sensitivity or alertness to occasion as to when to clean their room, when it's time to clean their room. So in a very silly way, if you put all those three things together, it's sort of the disposition for cleaning one's room.

But we're talking about innovation, invention, we're talking about higher order processes, and it's kind of developing that skill to find opportunity and to have the ability to affect change. It's wanting to do that, having the motivation to do it, and then it's seeing opportunities as to when to do that, to be sensitive to those opportunities. And research has found that developing the skills of creativity and the motivation for creativity

Those aren't the tricky parts. The tricky part is the sensitivity piece, knowing when to employ those ways of thinking. They call that the bottleneck of dispositions, to quote Project Zero Theory there.

Susan

So I'm curious how you get around that bottleneck. How do you break through it? Because that is, to your point, I think that's when we work with teachers who are working with arts integration, for example. Many of them want to do it. They can do it. But they hit that bottleneck when it's looking for opportunities to connect one subject to another. Some people are naturally gifted in that, in that they immediately see the connection between you know, Hamilton and a theater concept, right? Like they immediately say it, whereas others could stare at that all day long and not ever see it until somebody else tells them. That was an example. So how do you bust through that bottleneck? What are some practical ways we can look at doing this?

Edward

I'm going say two things, and I think you've identified this perfectly. So what research has shown is kind of, or one of the suggestions is the reason we have that bottleneck is because within schools, especially here in the United States, but it also takes place in other environments as well, within schools, children are told when to think and how to think. In math class, think mathematically. In this class, think analytically. During research play, I mean recess play.

But when are children in school, throughout their school way, given the opportunity to think for themselves? So I think one piece is providing young people more open and flexible opportunities within their learning day to think for themselves and make their own decisions and choose what kind of modalities to think. Remember, we're talking about the profiles participation. There's not just one way to engage in invention and innovation. There's many ways.

So how do we provide spaces for young people to engage their different strengths and abilities or to challenge themselves and to engage in creative idea development in different ways? So one of them is finding the space to enact what myself and my colleagues might call individual and collective agency. So when are we giving young people the space to really understand that they have individual and collective agency? And that is by helping them understand that they're not just the consumers of their experiences, they can be the creators of their experiences. But the way that school is set up, the way that maybe even our life in Western culture is set up, is that we're presented with worlds around us and asked to just kind of follow their rules and consume them. And it takes an extra effort to see yourself not just a consumer of your experiences, but a creator of your experiences. And that leads to my second piece, which is supporting young people and having a sense of systems thinking. Because all of that connects to understanding the systems that are around you, the different parts of the system, the purposes of those parts, how those parts and those purposes interact, who are the different people in the system, what are the different needs and desires of those individuals, what do they think, feel, and care about their roles within the system. So the more that young people can develop a sense of systems thinking, the more that they can see themselves as agents of change within those systems. So that's a tall order, but to answer your question, I think we need to provide young people with more spaces where they can enact their individual and collective agency, where they can see themselves not just as the consumers of their experiences, but as the creators of those experiences. And at the heart of all that is to having the sense of systems thinking, to understand that not only is the stuff that we engage with made and developed, but also the systems that we participate in are made and developed by other people and therefore can be hacked or redesigned by ourselves as creative actors within that space.

Susan

100%. I feel like I work with lot of grantees and who are working on establishing systems in schools for a variety of purposes. And one of the things that we work on with grantees as adults is systems thinking, because many of us did not understand that or have that in school, in our traditional school atmosphere. I also think that, to your point, that some of this doesn't have to be major steps like, for example, we often promote using common vocabulary walls across your classrooms, right? That's a simple, easy way for students to see that there are words that transcend outside of math class, science class, English class, that there are words that are common across all of them and the arts and that these are ways that we can play with the concepts of that in a variety of ways that can begin that agency. I am curious, I know our audience is really practical, and so I'm wondering if somebody is listening who's saying, this is amazing, I would love to do this, but I have a scripted curriculum and a pacing guide that I have to adhere to in my classroom, how can I bring more creative agency into my classroom or give the opportunity for students to explore these things when I have a set curriculum and pacing guide that I'm required to follow.

Edward

Sure, I'm going start with the third grade classroom. So we've got colleagues who work at schools in the Midwest, in Michigan, and a good friend of mine, Julie Rains, and her colleagues over there, they're very familiar in the third grade curriculum. There's always a biography unit. You have to do a biography on some creative individual or some prominent individual, usually from your community. And if you're in Michigan, it's usually going to be Henry Ford, right? So all the kids right there, third grade, five paragraph essay on the life of Henry Ford. But my colleague, Julie, and her friends said, well, what if we didn't write our biography on Henry Ford? Let's explore, what is Henry Ford really most known for? just that and the other, cars, mass production. Great, mass production. Let's do a biography of mass production instead. And then the kids, you know, they write their third grade five paragraph essay on the history of mass production and they realize who the different people are who contributed to the development of that idea. And Henry Ford was only one person who played one role at a particular time, but many people played different roles within the development of the idea of mass production. If you're really going to go down that path with third graders or others, you're going to say the white guy that was Henry Ford, you know, also took advantage of the many African-American people who worked before him or worked alongside him to develop this concept and everything. And you're going to break that apart and have other topics to explore within these complex systems. So that's one way to do it. In the recent book that my colleague Julie, who I've been referencing and I've published called the Participatory Creativity Guide for Educators, that tool is called From Individuals to Ideas. And it's a step-by-step guide on how you can engage in the process I've just briefly described, probably not as eloquently as Julie could have done it. Another tool that's developed by our colleague Joyce Pereira, and she's at the international school of Korea in South Korea, she developed this tool that she calls, I believe, Looking Backwards to Move Forward. And again, this is in the Participatory Creativity Guide for Educators book.

So Joyce teaches this course called Looking Backwards to Move Forward. And Joyce teaches a computer science course. Kids join this course, they're interested in inventing apps, they wanna code and do all this stuff. And Joyce says, whoa, slow down. Before we get to developing the next great app or the next great gadget, let's think about why we're doing this. So she'll start with something like an iPhone or a smartphone. And she'll say, before we think about what the next chapter is for the biography of this idea, let's trace it back to its origins. And she starts with something she calls the human need. So what is the initial human need that the iPhone or smartphone came from and kids might identify something like to be able to communicate across the distance. And then Joyce will say, okay, everybody, let's figure out what were the first iterations of products or systems or methods for communicating across a distance. And we'll have smoke signals. We'll have like, you know, tying a message to an arrow and shooting it across a canyon. We'll come up with carrier pigeons, you know, all of these things. And then she puts this plus and minus.

Well, what was good about that next iteration and what was not so good and needed improvement? Okay, so we'll move on from smoke signals to carrier pigeons. What was good about that? What needed improvement? Okay, we'll move on. How did they address that, you know, area of improvement work all the way up to our current day device and say, what problem did this device solve, but where can it be improved upon? So she's having young people think across this arc of time and understanding that they're not just going to come up with the newest, greatest thing, but that they're always connecting that towards that human need that came from the whole strand of inventions and innovations along the way. And from a participatory creativity perspective, we would say that all of those different iterations are artifacts of the creative idea of communicating over a distance. So always focusing on the idea which wends its way in the world and takes different shape over time. But the actual things associated with the idea are artifacts of the idea. And this is especially true with artworks. You when we think of a particular painting on a wall or a sculpture in a museum or a video piece, those are artifacts of greater ideas. They're not the creativity themselves. They're just artifacts of idea.

Susan

Well, and I could keep talking to you, I think, for hours, but we're running out of time. for those who want to stay in touch with you and dive deeper into your work, where can they find out more information?

Edward

Shamelessly plugging books. So check out the most recent book, The Participatory Creativity Guide for Educators by myself, my good colleague, Julie Rains. Check out the original participatory creativity book. That's called Participatory Creativity, Introducing Equity and Access to the Creative Classroom. Go to the project zero website. Also check out the website for my new learning and development organization, The Next World Learning Lab. Instagram, kind of LinkedIn, all the familiar places, you'll find us there and always happy to engage with you, your listeners, and with anyone else interested in talking about creative idea development.

Susan

Fantastic. As always, we will put that in our show notes so that everybody can find everything in one spot. Edward, thank you so much for your time today. I sincerely have learned so much from you and I am so grateful that you've expanded my own creative capacity today.

Edward

You got it, Susan. Always my pleasure. Thank you so much.

Susan

Of course.