ART WORKS FOR TEACHERS PODCAST | EPISODE 041 | 31:57 MIN

How to Craft Better Questions

Enjoy Maverik Education’s 60 Second PD on Deconstructing Standards.

Alright, welcome Eric to the podcast. I’m so excited that you’re here today.

Erik

Thank you. Thank you very much for having me today. It’s my honor and my privilege to be here.

Susan

Of course. So I always like to start with the assumption that people don’t know who the heck I’m talking to. So would you please introduce yourself to our audience? Just share a bit about yourself and what you do.

Erik

I’m actually going into my 28th year. I’ve been a middle school and high school teacher. I’ve been a site administrator. I worked for State Education Department in Arizona.

2012, I decided to go break out on my own and provide professional development and guidance support to schools. I formed my own company. It’s called Maverick, M-A-V-E-R-I-K. No C in Maverick. I’m not Tom Cruise. I’m Eric Francis. So it’s a play on my name, M-A-V-E-R-I-K. It’s also named after my daughters, Madison, Avery, and Amanda. And yes, I am a fan of Tom Cruise and Top Gun. So that’s also part of who it was named after.

What I do is based on things that I did when I was in the classroom. And one of the things that I did was I asked what I call good questions. And there’s a specific thing about what makes a question good. And so what I did with it was that I used questioning not just to assess, but also to activate advanced learning. And it was a method I used in all the subjects I taught. I taught all the subjects, basically, you know, gave up my prep time to go teach on my content area to make extra money. And I would ask the kids questions and they would teach me actually. So it’s a method I use, it’s a method I wrote about I wrote in a book called “Now That’s a Good Question: How to Promote Cognitive Rigor through Classroom Questioning” was published by ASU in 2016. And it’s also become a strategy that I use with another concept that I probably have a lot of professional development on called depth of knowledge, DOK.

Depth of knowledge clarifies and confirms the cognitive demand of academic standards, curricular activities, and assessment items. But questioning is what we use to get the kids to learn at different and deeper DOK levels. It’s not about the level of thinking. It’s the rigors and the response. So what I like to say about depth of knowledge is that there’s four levels. At level one, you’re attaining the answer. At level two, you’re explaining the answer. At level three, you’re justifying or verifying an answer, which means there could be more than one. You have to basically prove whether it’s valid or invalid, correct or incorrect or accurate or inaccurate, and a level four you extend the answer. So that’s what I do. I provide professional development support. I work with schools. I come in as a troubleshooter and a problem solver, not as a savior, not coming in saying, here I come to save the day with a big Superman on my chest or M for Maverick.

and really try to work with teachers and really try to work with schools to make teaching and learning what I like to say is standards-based, socially emotionally supportive, and student centered. And so we have to shift how we look at things. It’s not what I teach, but it’s what exactly must the kids learn and how deeply must the kids understand and use their learning. I mean, we’re teachers, we teach well, we know our stuff.

And we justify what our kids are doing based upon the complexity of the skill. But it’s not what we’re teaching. It’s what must the kids learn and how deeply must they understand and use their learning. That’s kind of the focus I do with my professional development to get out.

Susan

That’s fantastic. And it’s something that’s so aligned with what we promote at the Institute because, you know, we sometimes call it the difference between fast food teaching and, you know, healthy food, healthy teaching, where, you know, there’s so much out there that’s edutainment and that’s kind of surface level. And that’s not to say that there’s anything wrong with that. I mean, everybody likes a good drive through at the McDonald’s every once in a while, right?

It’s, but it’s, is that healthy for us? Is that the best, most nourishing way that we can be teaching our students? And so it’s not, we know that. And so standards-based learning, being able to make those connections and then facilitate deeper conversations and rigorous thought is really where we need to be headed, particularly with all of the the changes in technology that are coming around the bend, racing at our heels right now.

So I love the work that you’re doing, particularly around questioning. And I wanna dive into your book, “Now That’s a Good Question” because, and our audience will know this, I ask people all the time, how do you ask a good question? What is a good question? How do you ask a question? How do you formulate that? And then how do you design them for our classroom? And nobody can give me this answer, so I’m really hoping that you can share some insights on that.

Erik

Well, it’s interesting because when you look at it and you say good question, you think that they’re supposed to be good questions and bad questions. It’s not what is a good question, but rather what does a good question do? And a good question, this is what I like to say, a good question stimulates different levels of thinking. Now, if you notice I said different levels of thinking, it’s okay to stimulate the kids to remember and understand.

And also I say, actually, remembering kids don’t remember stuff. They remember experiences. So if we go back and think about our school, what we remember, we, we remember how to read, write and do the math because we attach it to an experience, like you can probably tell me who taught you how to read, who taught you how to write, who taught you how to do basic arithmetic and what class was in it, when did it happen? But as we get older, the remembering focuses more on stuff and not the experiences we give. Like think of, you don’t think about that test you took on ratios in sixth grade. Or, you know, but you think about when your teacher had you use ratios in some sort of experience and that’s how you have that deeper understanding. So a good question stimulates different levels of thinking. It can be used to check for and confirm knowledge, understanding and awareness. And that’s typically what we use with questions.

What’s interesting I like to say is that children between the age of 2-5 and research has shown this. They’ll ask like 300, 500 questions a day all to their mother, you know, because that’s the state for adult. When they go and it’s because also brain development, their frontal lobes are developing so fast. That’s why kids are always saying why, why? And what’s really interesting is that the questions in school are not really used to activate advanced learning, but assess learning. The emphasis is on the answer, not addressing the question. That’s how school, I do say that in schools we kill questioning. It’s because there’s such a pressure to give an answer.

When I ask a question, I don’t expect you to have an answer. I expect you to think about it. I encourage you and engage you to think about what I’m asking. And that’s another thing where questions do. They basically expand knowledge and extend thinking. Like, if I asked you a question, if I said, how did Edgar Allen Poe create an entire genre of literary fiction? Now, unless you have expertise in Edgar Allen Poe, you wouldn’t know. And that’s OK.

And that’s another thing. There’s some people saying, we don’t want the kids to say, I don’t know. Why? It’s okay to say, I, D, K. Okay? It’s okay to say, I don’t know. Because what you’re doing is, you’re opening a door to learning. I’d rather a kid not know than a kid think they know everything, or a kid knows something, and it’s not accurate, and it’s not valid, and it’s based more on feeling than iis on factual evidence and logic and ethics and support. So that’s the okay. So when I ask you that question about Edgar Allen Poe, that’s also what a good question does because not only did I expand your knowledge and extend your thinking to say like, wait a minute, I never knew about this, but I’ve also piqued your curiosity, imagination, interest and wonder. Cause now when I said that to you, the look on your face, your eyes widened and you’re like, what does he mean by that? And I got you.

I hooked you. And that’s the other thing is that you want the kids to be able to express and share their learning in their own unique way. That’s what a good question does. It allows for communication. It presents the instructional focus not as a standard or an objective. And some people think when I say compare and contrast how or explain why, that’s not a question. I’m telling you to compare and contrast how. I’m telling you to explain why.

I’m not asking you. It’s not inviting you. So it basically presents the instructional focus as a question and it also prompts people to reflect before responding. So again, when I ask you that question, you might be thinking, wait a minute, I don’t know. What do you mean by literary genre? What literary genre did he create?

And I’d say, well, what if I told you that Sir Arthur Conan Doyle created Sherlock Holmes admits that he actually based Sherlock Holmes on a character Edgar Allan Poe created 40 years earlier. Look how much stuff you learned. And I taught you absolutely nothing. All I did was ask you questions. And that’s the big secret behind it.

Susan

And it sounds like when you’re asking questions, you’re almost tying it into storytelling as well.

Erik

Mm-hmm. And also you want them to really think about it So if I ask you let’s say for math if let’s say I said what is two plus two you would tell me what?

Susan

Yeah.

Erik

What do you mean? That’s the important thing. Like when I have teachers say to me, well, the kids don’t know their multiplication facts. Well, why do they need to know their multiplication facts? Because everyone needs to know their multiplication facts. No, they don’t. I can do it on a calculator. I can do it on a computer. OK? Technology has made answers free. The problem is we don’t know how and why that’s the answer. And we talked a bit before we got on. I know you mentioned ChatGPT and Google.

Here’s the thing, it’s changed the way we do things. You and I are part of the same generation. We learn from our teachers. And if our teachers asked us a question, we better answer it the way they taught it. But now we have critical thinking. Google is basically what we call a DOK1, a level one. Because it can give you the answer. I can ask Google, I can ask Alexa or Siri on my watch here on my phone, and it’ll give me an answer.

Chat GPT is what we call a DOK2 because it can explain to you in a human voice. What Google and Chat GPT can’t do is they can’t justify, they can’t rationalize or defend with reasoning and they also can’t extend learning. And so you do arts integration. I can write a movie script in which I say I want to do it where Batman meets Iron Man, but Chat GPT will just do it.

But there’s a lot of thought that has to go into, because wait a minute, there are two different universes, there’s two different comic book companies, how do I do this? And people might say, who cares? But that’s what we care about, that deep learning. And that’s what questioning will do with you.

Susan

Absolutely. So is there a process that we could use or that we could explore to help us design better questions or questions that get to the heart of what we want our students to be able to share with us?

Erik

Yes, so here’s the thing. We as educators need to shift how we deliver our instruction. With education, traditionally and generally, I’m making generalizations, we do three things. We present information, we provide instructions, and we post questions to assess learning. What I’m asking people to do is to ask questions, not that students have to address, answer, excuse me but address. So when I ask you a question, it’s to activate and advance your thinking. If I had an MRI in front of your head, your brain would start lighting up because your brain is starting to think. The simplest thing to do is this. I want everyone to take their standards or I want everyone to take their learning targets and say, I can, and it’s usually followed by an imperative statement, a command. Put, “how could you” in front of all your objectives, you will now have a question. Watch. If the standard says, fluently multiply multi-digit numbers using the standard algorithm, I’m going to put, how could you in front of it? How could you fluently multiply multi-digit numbers using the standard algorithm? Now you’re looking at it like, OK, now I see this as a question. And the standard can be the question. Now you’re not relying on the 25 items you give the kids. Now you’re relying on that question and the items become your supporting examples and evidence, not your measures. Because I can give you 25 problems today and you can solve it successfully because today’s a good day. Now we come back together another day and you’re having a bad day and you can’t do that 25. Well, wait a minute, you did 25 the other day. Why can’t you do these 25?

Cause I like to say it’s either Ice Cube or Daniel Powder: today was a good day or you had a bad day. So, and that’s that deeper learning. So that’s my big question. Big thing for everybody. Put “how could you” in front of all your objectives, you will turn your imperative statements into interrogative ones. Instead of saying, I can as a learning target, or we will, ask say, how could you? And how could you get that deeper strategic thinking?

How do you is more of a recall. And you can do that. How do you fully multiply multi-digit numbers? How can you is more instructional, but how could you is more inquiry.

Susan

That’s so wonderful. And I love that just that easy small shift because not only does that help you build better questions to ask your students in real time, but it’s also a way to rethink how we’re designing our lessons. So we’re looking at that standard and we’re thinking about all of the different ways that we could then help students to explore that question and offer them different alternative methods instead of just a direct teaching. Perhaps direct teaching is warranted in it, but it might be they need a project-based learning experience, or they need an arts-integrated experience, and you could then use that prompt, just that small shift, to rethink how you’re presenting the information for students in a way that they can engage with. I think that’s such a fantastic, small tweak that just has big possibilities.

Erik

Mm-hmm. And you’re personalizing the learning, okay? It’s, it’s, because don’t say, how could I, because the kids can turn back and say, “I don’t know teacher, how could you?” And don’t say, how could we, because then it’s collective and you lose that individuality. But say, how could you? It can be collective and can be individualized.

That’s the big thing we want to basically do. The other thing I would also recommend everyone do is that every time your kid gives you an answer, say, what do you mean? Okay, don’t say, how do you know? Because that’s a challenge, okay? And that’s basically you’re throwing down a gauntlet. What do you mean is inviting you to elaborate, to explain? This is actually, my father taught me this because he told me, don’t just ever just take statements, have people explain their thinking and reasoning. And it actually helped when I actually would have… sometimes parent, you know, I get a parent complaint. I mean, look, it’s education, we get parent complaints. And that parent would come and say, you don’t like my child. And I’d say, what do you mean? And the parent would say, why are you asking me, what do you mean? I said, because I need examples and evidence so I can either explain myself or apologize. So finally, then this is actually a true story. What happened is that parent did this.

And the root of it was that the child didn’t like me anymore. They didn’t find I was funny and wanted out my class. That was the root of it. And what I said was, what do you mean? So because what you’re doing is you’re showing you’re caring. You’re not challenging, but you’re caring. When I asked you, what do you mean about two plus two, I’m asking you that because I want basically to understand the depth of your knowledge. Because if you can tell me what two plus two is, then I’d say, okay, now what if I added three zeros after your twos, what would I have? 4,000, why? Because I take 2,000 combined, see? And that’s the thing, when you talk about arts integration, everything that’s created starts with a question that asks what if, okay? And that’s the thing, what if a beachfront community was terrorized by a giant shark? Guy Peter Benjamin writes Jaws, okay?

Um, what if I painted this picture where I just put splatter on it and made these designs? You have a Jackson Pollock, you know, design. Okay. That’s the other thing is that basically your three things is put, how could you in front of your standards? Ask, what do you mean? Every time someone gives an answer, ask what if to think creatively. And when you lecture, instead of lecturing, saying, Edgar Allen Poe wrote the first detective mystery story. What if I told you, that Edgar Allen Poe wrote a detective mystery story. That’s how we can get questioning.

Susan

That’s great. I wanna talk a little bit about the word engaging because we keep hearing this over and over and over, particularly now after having two, three years of pandemic and needing to engage our students. I feel like it’s thrown around a lot, but that engaging doesn’t necessarily translate into learning. So I’d love to know what engaging looks like and sounds like to you in a classroom. What does that mean, engagement to you?

Erik

Can I get the kids curious? That’s engagement, okay? I taught English language arts, and I taught American Lit. And I had to teach literature that is over 150, 200 years old. My challenge was, how can I connect what these works are and know why we’re reading it. Okay, so for example, I used to tell the kids when I taught Scarlet Letter, I’d say, how does the Scarlet Letter adjust the theme of guilt? Stereotypically, socially, religiously, and psychologically through the four main characters. Now that’s a connection because kids understood what guilt is and we would have discussions. What is stereotypical guilt? What’s social guilt? What’s religious guilt? What’s psychological guilt? Which of those characters embody that? And they got it.

And it made them want to read it. The other question I asked them is, why is the modern day Scarlet Letter TMZ and what are the similarities between Hester Prynn and Kim Kardashian? And we would go into it and I’d say, tell me about Kim Kardashian. And the kids would tell me, and I’d say, now using appropriate language, tell me about Kim Kardashian. And I said, there’s a word for that. And… It’s called scan… They go scandalous. I go right. I said, now she had a scandal and what did she do with her scandal? She turned it into success. So she took her scandal and turned it into success, something that’s respectful. And you learn is there’s so many things here. Shakespearean tragic hero is all about the noble person who falls from grace. And I used to have my kids, I’d say to them, I’d say, what is an example of a literary fictional character, a real life person who is a Shakespearean tragic hero?

And I would have the kids tell me like, OJSimpson, which led into a thing like, okay, you guys want to read Othello? Cause that’s what they actually based it on. And what I’m doing is, is I’m getting the kids curious. I’m getting the kids connected because they see the connection to their real life. And by being curious and being connected, they’re interested, okay? And it all comes from questioning. Questioning is not what do you know?

Questioning is all about is this what if this is something you’ve never really thought about and considered before

Susan

Mm, I really like that so much. And I also love how you really do personalize it to them so that they can make those natural connections. Before we go though, Eric, I wanna respect our time today, but I have to say that on your website, which we’re gonna link in the show notes, you have this great section called 60 Second PD, which for teachers who are just slammed for time, it’s so helpful.

You have one about standards and deconstructing standards, and I would love for you to walk us through a 60 second PD of deconstructing standards, because I think this is some of the most difficult work that teachers have to do. We find that in our certification program a lot, that when we get to standards, teachers are like deer in headlights sometimes. So I would love a 60 second PD on deconstructing standards.

Erik

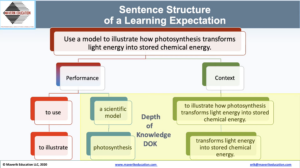

Okay, so it is an extension of the traditional Larry Ainsworth method where you circle verbs and underline nouns. And it’s kind of funny because this is actually a PD I just did and it’s actually in my wheelhouse right now and actually it’s gonna be in my next, next book. So what I say is this, you look at a standard and I want you to underline all the content words you see. That’s the stuff you need to teach and the stuff the kids have to learn. Okay, those are called DOK1s.

Then I go and look for my verbs, or my cognition words. Not just verbs, cognition words. Now I gotta understand and inform the context. That’s what exactly and how deeply students must understand and use their learning. That’s what determines the depth of knowledge demanded. So first thing you ask, what are the content words? Okay, then you say, what is the cognition words? Then you say, what are the words and phrases that establish the context? What exactly and how deeply? You take a highlighter and you highlight everything that follows that first verb. Now, there might be verbs in that highlighted area. You know what that means?

You have two objectives or three objectives you have to achieve to demonstrate proficiency or there might be multiple contexts. So your question to this, what are the content words? What are the cognition verbs? The thinking that they have to do? What exactly and how deeply do they have to do it? Highlight everything after the verb. How many objectives are in that standard? And repeat steps one, two, three.

Susan

Awesome. So succinct and so helpful. Thank you so much for that. And it’s true. We talk about that a lot about looking for cognitive demand and how to break that down, but you just make it so easy. So I so appreciate that. Before we go…

Erik

Yeah, the question I have about that is that basically we may be teaching the standards but our kids hitting the bullseye. And I represent it. So if you notice, I said red, blue and yellow. So the blue is the outer and it’s, these are the colors of archery. So the blue is the outer circle. That’s the stuff I get closer to the bullseye with the red. That’s the skill. But what’s the situation stipulations in which they must understand and use the subject and skill.

That’s the bullseye, that’s everything in the yellow. So that’s what I ask teachers. We may be teaching a target, but are our kids hitting the bullseye?

Susan

The last question, I always ask everybody this, if there’s one thing that you would like teachers to know about creativity or curiosity, what would it be?

Erik

… It is natural and it is innate and it has to be tapped into. And it has to be something that is, I’d also add in there, not only creativity and curiosity, but confidence and courage. A lot of reasons why kids don’t get creative because they’d say stuff like, ah, nobody would care about that, or ah, that’s a dumb idea. No, okay. I mean, every idea is a potential great idea.

You know, every thing that, you know, that piece of paper you threw out was probably genius. I mean, Stephen King’s wife took Carrie out of the basket and that’s how he got it published. You know, Walt Disney was drawing on a napkin this rat, okay, that he called Mickey Mouse. That’s the thing. So I would say basically it’s not just about creativity and curiosity. It’s about courage and confidence to go pursue your creativity and curiosity. And you don’t have to be the best. Just have fun.

You know, I’m a huge fan of Van Halen and I just listened to these interviews with Eddie Van Halen and his whole purpose of playing guitar was to get the sound that was in his head out through some sort of musical instrument. I played guitar, sometimes he played piano, sometimes he played cello, but he just wanted to get it out. And that’s the thing is that trust what you believe, trust what you feel.

And to tell you the truth, more often than not, the more time, the more creative it is, the more misunderstood it would be, and it must be genius. But your challenge is, how can you have it where people can understand and recognize and realize what your creativity is and be aware of your audience? And I say it to my students all the time because my students would say, you know, if I gave them a grade, they’d say, well, you just don’t understand. I said, yeah, I don’t. You have to respect your audience because you can sit in your room and say,

You wrote the greatest song since, you know, Sergeant Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band and Dark Side of the Moon, Pink Floyd. And if no one understands that, you’re just going to be sitting in your room doing that. So you have to have an appreciation of your audience too. So that’s what I would say about creativity and curiosity. What is, you know, what is it that really makes me excited? How can I do this in an innovative or inventive way? But…

I also, how can I be courageous enough to go and confident enough to know that I’m going to put this out there. There’s some people like it, there’s some people who won’t, but that’s okay because I feel good about it.

Susan

Where can people find you and stay in touch?

Erik Oh, that’s a good question. Okay. You can go to my website, www.maverik.com. You can also email me at erik@maverik.com. I have two books. One is published by ASCD. It’s called “Now That’s a Good Question, How to Promote Cognitive Classroom Questioning.” And my other book is called from Solution Tree, called “Deconstructing Depth of Knowledge and Method and Model for Teaching and Learning.” But if you go to my website again, Don’t put a C in Maverik, that will take you to India. Okay? Maverik, M-A-V-E-R-I-K, education.com. That’s the best way. Or catch me at conferences. I’m usually presenting, I’m presenting a few places. I’ll be at the University of Connecticut Confertude Gifted Conference in a couple of weeks. I’ll be at the National Secondary Schools for Principals Conference, and also the Southern Region Educational Board High Schools at Work Conference this summer. So, but if you want to keep in touch with me, contact me. All my information is right there on my page.

Susan

Fantastic, thank you so much. We’ll make sure to put that into the show notes as well so that people can easily click on that link and just get straight to you. Erik, thank you so much for your time today. I really appreciate it. And thank you for sharing with us how questioning can really change everything.

Erik

Awesome, I appreciate you having me on, thank you. It’s been an honor and a privilege and I really appreciate it.

Susan

Of course.